Lo oscuro, seductor: Aproximación a la obra de Marco Mazzoni

Por Juan Pablo Torres Muñiz

Desde El Bosco y sus paisajes oníricos poblados de criaturas híbridas, hasta el mal llamado surrealismo de Remedios Varo o el supuesto realismo mágico de artistas contemporáneos como Ray Caesar, la exploración de los límites entre lo reconocible y lo imaginario seduce, al parecer, inagotablemente. Lejos de ser un escape de la realidad, la propuesta opera como un dispositivo crítico: al presentar lo imposible con la nitidez de lo real, fuerza al espectador a cuestionar los marcos conceptuales desde los que habitualmente interpreta el mundo. En este contexto, la obra de Marco Mazzoni se erige como un ejemplo destacable, no solo por su destreza técnica —que evoca la precisión de los maestros flamencos y el detallismo botánico de ilustradores científicos como Maria Sibylla Merian—, sino por la hondura de su articulación simbólica, que trasciende por mucho lo decorativo o provocador. Mazzoni interroga con elocuencia, especialmente en lo tocante a la femineidad, la naturaleza, lo sagrado y los límites de la razón normativa.

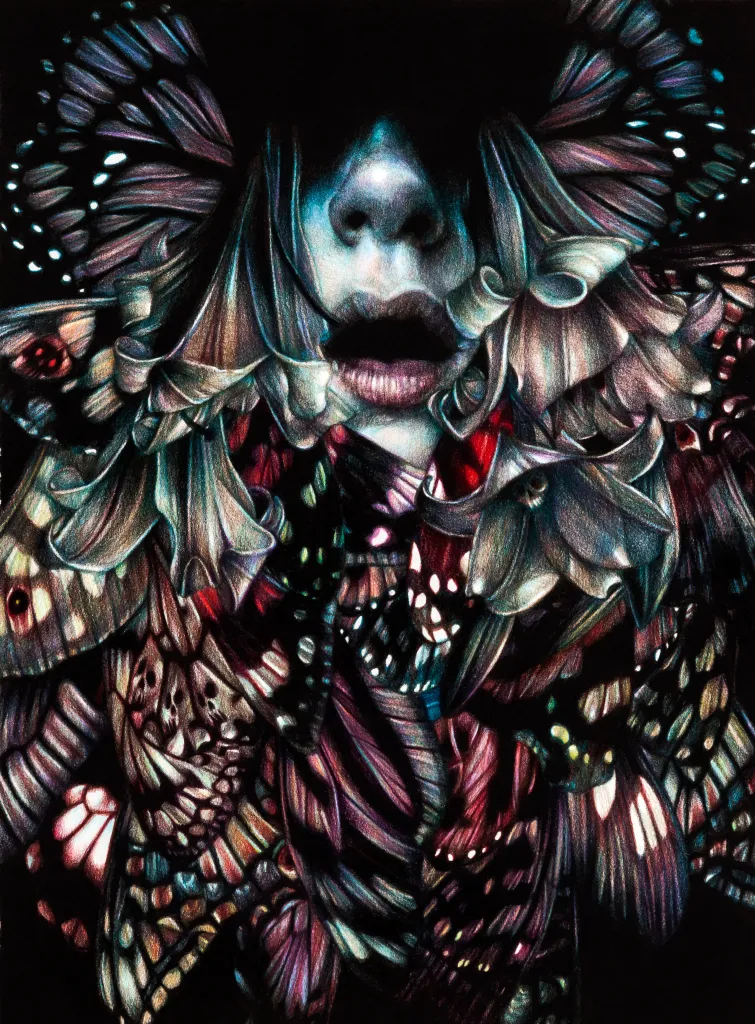

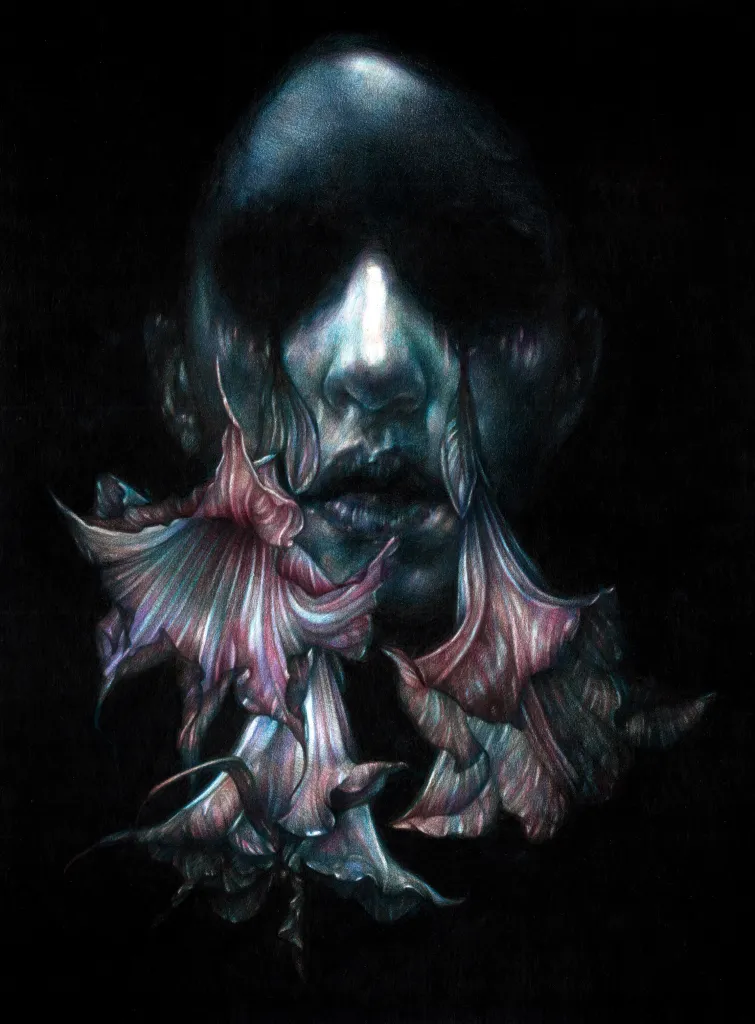

La temática central de Mazzoni gravita en torno a la figura femenina, casi siempre presentada en simbiosis con elementos de la flora y fauna silvestres. Sus retratos, ejecutados con lápiz de color sobre papel, muestran rostros de mujeres cuyos ojos suelen estar velados o cubiertos por mariposas, flores, hojas o insectos. Algo en lo que fue pionero y por lo que ha sido seguido e imitado hasta el escándalo. La ceguera impuesta no sugiere una carencia, sino una forma de visión alternativa, interior, intuitiva. La mujer en Mazzoni encarna, más que una supuesta fuerza ancestral, a la vez creadora y destructora, un primitivismo atávico, fundido con el entorno natural hasta volverse indistinguible de él. Este vínculo entre lo femenino y lo vegetal —raíces que se confunden con cabellos, pétalos que brotan de párpados, enredaderas que trepan por cuellos y torsos— niega la naturaleza como recurso inerte y dominable, tanto como el enfoque de la feminidad como algo delicado, subordinado gratuitamente. Mazzoni devuelve a lo femenino su carácter salvaje, fértil y caótico, en sintonía con una naturaleza que es tanto refugio como amenaza, matriz de vida y tumba. Lejos de una idealización bucólica, ofrece una suerte de reivindicación de lo oscuro, lo cíclico y lo irracional que habita en ambos ámbitos. La paleta de colores, dominada por tierras, verdes profundos, azules nocturnos y rojos opacos, refuerza esta lectura: la oscuridad, no como mal, sino como misterio… de lo que yace bajo la superficie de lo aparente, de los secretos de una vida que escapa a la comprensión y el control civilizados.

Desde luego, aquí vemos también en entredicho, la medicalización del cuerpo de la mujer y la religión organizada. En muchas de sus obras, Mazzoni expone referencias veladas a figuras como las brujas —sabias curanderas perseguidas por su conocimiento heterodoxo— o a divinidades paganas anteriores al orden judeocristiano. Mazzoni recupera, ambiguamente, un tipo de paganismo matrístico donde lo sagrado reside en la inmanencia de un mundo material habitado por fuerzas que no distinguen entre bien y mal, sino entre crecimiento y decadencia, entre floración y putrefacción. La vida, en su obra, es un proceso orgánico, apasionado y antiético, que incluye tanto el nacimiento como la muerte, lo bello y lo grotesco. De este modo, propone una visión integradora, no por ello menos inquietante: la naturaleza —y por extensión, lo femenino— no como aliada del ser humano, sino como fuerza autónoma, indiferente a sus razones y moralidad, capaz de nutrirlo y, a la vez, de devorarlo.

La técnica de Mazzoni es, en sí misma, un elemento central de su discurso. Su medio predilecto, el lápiz, le permite una precisión minuciosa que recuerda a los dibujos de los antiguos naturalistas. Cada pétalo, cada ala de mariposa, cada hebra de cabello, con un nivel de detalle que bordea lo obsesivo. Todo al servicio de la ficción simbólica: el realismo extremo busca dotar de credibilidad a lo imaginario. La textura del papel, a menudo visible, aporta una cualidad táctil y orgánica que refuerza la sensación de estar ante algo vivo, en proceso de crecimiento o descomposición. Mazzoni no utiliza líneas negras para delimitar las formas; en su lugar, superpone capas de color para crear volúmenes y sombras, lo que confiere a sus figuras una cualidad etérea, como si emergieran de la oscuridad o estuvieran a punto de disolverse en ella. Esta técnica de difuminado y superposición contribuye a la ambigüedad narrativa de sus obras: no sabemos si estas mujeres despiertan, duermen, mueren o se transforman. El uso predominante de colores terrosos y oscuros, interrumpido ocasionalmente por destellos de rojo carmín o amarillo oro, evoca la paleta de los manuscritos iluminados medievales, estableciendo un diálogo tácito entre su obra y la tradición del arte sacro, pero subvirtiendo su iconografía: aquí, lo sagrado no está en el cielo, sino en la tierra, en el cuerpo, en el ciclo eterno de la vida y la muerte.

Mucho más que por su novedad formal —pues bebe de fuentes clásicas y modernas—, es por la coherencia y profundidad con la que se articula, que esta obra merece especial atención. Nada de regresos románticos a un pasado idílico, si no, más bien, la tentación de una reconciliación con la parte oscura y cíclica de la existencia, con todos sus riesgos y contradicciones. Es lo que trae consigo el perfume del bosque, la noche misma. Seducción.

[Todas las imágenes, del sitio web del artista: Marco Mazzoni – Marco Mazzoni Art]

ENGLISH VERSION

The dark, the seductive: An approach to the work of Marco Mazzoni

Translation by Rebeca Sanz

From Hieronymus Bosch and his dreamlike landscapes populated by hybrid creatures, to the misnamed surrealism of Remedios Varo or the supposed magic realism of contemporary artists like Ray Caesar, the exploration of the boundaries between the recognizable and the imaginary seems inexhaustible. Through more or less outstanding technical mastery, they construct believable universes that nonetheless defy the laws of nature and everyday logic. Far from being an escape from reality, the proposal operates as a critical device: by presenting the impossible with the clarity of the real, it forces the viewer to question the conceptual frameworks from which they usually interpret the world. In this context, the work of Marco Mazzoni stands as a remarkable example, not only for his technical skill—which evokes the precision of the Flemish masters and the botanical detail of scientific illustrators like Maria Sibylla Merian—but for the depth with which he articulates a personal and symbolic imaginary that transcends the merely decorative or provocative. Mazzoni questions with eloquence, especially concerning femininity, nature, the sacred, and the limits of human reason.

The central theme of Mazzoni’s work revolves around the female figure, almost always presented in symbiosis with elements of wild flora and fauna. His portraits, executed with colored pencil on paper, show the faces of women whose eyes are often veiled or covered by butterflies, flowers, leaves, or insects. Something in which he was a pioneer and for which he has been followed and imitated to the point of scandal. The imposed blindness does not suggest lack, but rather a form of alternative, interior, intuitive vision. The woman in Mazzoni embodies, more than a supposed ancestral force—at once creator and destroyer—an atavistic primitivism, fused with the natural environment until becoming indistinguishable from it. This link between the feminine and the vegetative—roots blending with hair, petals sprouting from eyelids, vines climbing necks and torsos—calls into question nature as an inert and dominable resource, as well as the view of femininity as something delicate, gratuitously subordinate. Mazzoni restores to the feminine its wild, fertile, and chaotic character, in tune with a nature that is both refuge and threat, matrix of life and tomb. Far from a bucolic idealization, he offers a kind of vindication of the dark, the cyclical, and the non-rational that inhabits both realms. The color palette, dominated by earth tones, deep greens, nocturnal blues, and opaque reds, reinforces this reading: darkness is not synonymous with evil, but with mystery, with what lies beneath the surface of the apparent, with the secrets of a life that escapes human understanding and control.

Certainly, here we also see called into question the medicalization of the female body and organized religion. In many of Mazzoni’s works, veiled references appear to figures like witches—wise healers persecuted for their heterodox knowledge—or to pagan deities predating the Judeo-Christian order. Mazzoni ambiguously recovers a kind of matristic paganism where the sacred resides not in a transcendent god, but in the immanence of a material world inhabited by forces that do not distinguish between good and evil, but between growth and decay, between flowering and putrefaction. Life, in his work, is an organic, passionate, and non-ethical process, which includes both birth and death, the beautiful and the grotesque. In this way, an integrative vision is proposed to us, though no less unsettling for it: nature—and by extension, the feminine—is not an ally of the human being, but an autonomous force, indifferent to its reasons and moralities, capable of nurturing it and, at the same time, of devouring it.

Mazzoni’s technique is, in itself, a central element of his discourse. His preferred medium, colored pencil on paper, allows him a meticulous precision reminiscent of the drawings of ancient naturalists. Each petal, each butterfly wing, each strand of hair is rendered with a level of detail bordering on the obsessive. All in the service of symbolic fiction: extreme realism seeks to lend credibility to the imaginary. The texture of the paper, often visible, adds a tactile and organic quality that reinforces the sensation of being before something alive, in the process of growth or decomposition. Mazzoni does not use black lines to delineate forms; instead, he superimposes layers of color to create volumes and shadows, which gives his figures an ethereal quality, as if emerging from darkness or about to dissolve into it. This technique of blurring and superimposition contributes to the narrative ambiguity of his works: we do not know if these women are waking, sleeping, dying, or transforming. The predominant use of earthy and dark colors, occasionally interrupted by flashes of carmine red or gold yellow, evokes the palette of medieval illuminated manuscripts, establishing a tacit dialogue between his work and the tradition of sacred art, but subverting its iconography: here, the sacred is not in the sky, but in the earth, in the body, in the eternal cycle of life and death.

Much more than for its formal novelty—for it draws from classical and modern sources—it is for the coherence and depth with which it is articulated that this work deserves special attention. Not a romantic return to an idyllic past, but rather the temptation of a reconciliation with the dark and cyclical part of existence, not without risks, nor without contradictions. It is what the perfume of the forest, the night itself, brings with it. Seduction.