Materialidad y contraste: Conversación con J. Carino sobre su obra

Con Juan Pablo Torres Muñiz

Si bien toda obra de arte valiosa lo es por su propia elocuencia, por su eminente potencia cuestionadora, por la forma en que pone en entredicho conceptos e instituciones del mismo marco institucional del que, no obstante, surge y al que se entrega, lo es, antes, por formar parte de un fenómeno comunicativo material, conformado por, aparte este par de elementos, otro: el del autor mismo de la obra y el observador, gente de carne y hueso, sensible y con ideas organizadas sistemática o asistemáticamente. En tal sentido, la voz de quien ofrece su visión a través de un medio de expresión artístico cobra especial relevancia, no para explicar, al caso, cada cuadro suyo, sino para arrojar nuevas luces para su entendimiento y comprensión, lo que implica reconocer su adopción de términos más o menos convencionales, algunos de ellos, esencialmente objetados en su obra. Y es que, lejos de la búsqueda de simples contradicciones, atender el testimonio de quien obra exige reconocer, siempre, que la visión del mundo del artista cobra sentido, intencionalmente, pero también a su pesar, en un marco racional en conflicto.

J. Carino, muy amablemente, nos ofrece aquí su voz, a propósito de algunas cuestiones que le planteamos sobre su más reciente trabajo:

¿Qué dices tú mismo sobre la geometría utilizada en tus cuadros? ¿Su función es esencial, o más bien la de una mera forma expresiva de algo más profundo?

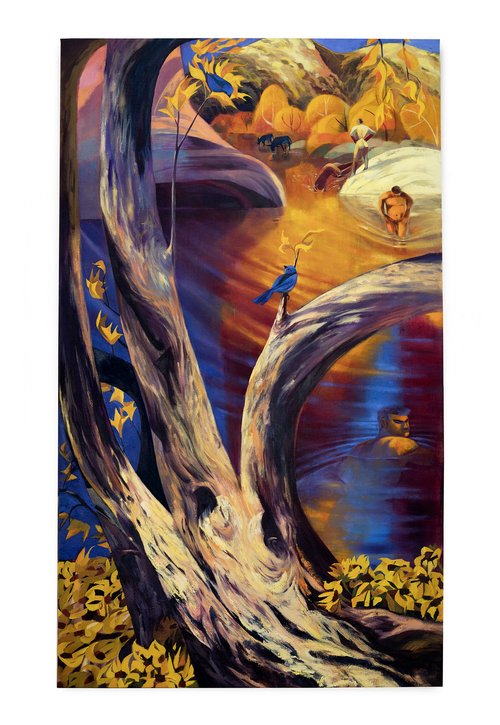

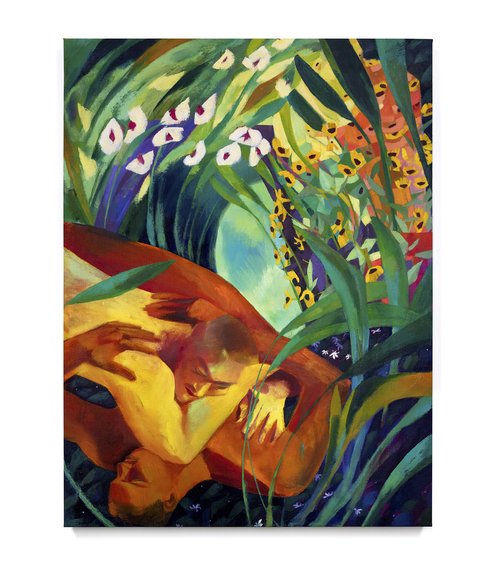

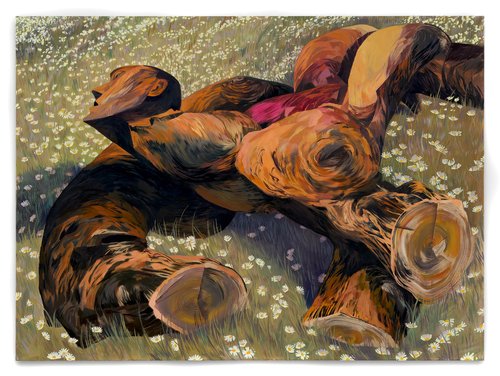

He estado reflexionando mucho sobre esta idea, especialmente en mi trabajo reciente, y hay varios niveles en la geometría de mis pinturas. En un plano, me gusta representar rocas, árboles, montañas y figuras humanas con el mismo enfoque, lo que a veces implica abstraerlas en formas más cubistas, fragmentadas y geométricas. Creo que esto genera un mundo en el que los límites entre lo humano y el «entorno» pueden ser menos rígidos. Ayuda a difuminar la línea entre una figura y un tronco de árbol, una roca o una ladera. En otro nivel, las personas queer a menudo llevamos vidas muy compartimentalizadas. Dado que nuestras vidas no son aceptadas en todos los lugares, separamos fragmentos de ellas para mostrárselos a ciertas personas en determinadas situaciones, y me gusta reflejar esa idea en la naturaleza compartimentada y geométrica de mis composiciones. Son paisajes naturales y salvajes, pero descompuestos en secciones de patrón y forma, en algunos casos casi como un collage, donde estas áreas permanecen separadas entre sí aunque formen parte del conjunto. Un aspecto sobre el que he estado reflexionando más recientemente es la manera en que esta forma de representar las figuras tiene una sensación casi digital o poligonal. En mi obra, aunque comento sobre el mundo moderno, hay muy pocos elementos que sugieran directamente la modernidad, salvo quizás una línea de bronceado de bañador o un corte de pelo contemporáneo. Sin embargo, creo que el enfoque geométrico con el que represento los cuerpos y los paisajes introduce un elemento de nuestro mundo moderno y tecnológico. Aunque a veces muestro edenes idílicos y sus habitantes pacíficos, estos reflejan de todos modos el estado tecnologizado y la manera de ver el mundo que hoy es inevitable. Todos estamos algo mitad máquinas, pegados a nuestros teléfonos, mientras intentamos volver a integrarnos en la naturaleza.

El cuerpo como materia: aquí se aparta un poco de la suavidad misma de la forma y revela, en el estilo pictórico, cierto afán por dotarlo de una consistencia diferente, acaso más sólida. ¿Qué dices al respecto?

Creo que mi representación de los cuerpos tiende claramente hacia la solidez y la monumentalidad. Me inspiran pintores como Tamara de Lempicka, Diego Rivera y Ricardo Martínez de Hoyos, quienes crearon figuras que parecen masivas y pesadas, casi como titanes o dioses. Me gusta que haya suavidad en el gesto o en la expresión, pero quiero que las figuras tengan ese tipo de cualidad heroica.

¿Qué significación le das al bosque, al menos en relación a los protagonistas de tus pinturas?

Creo que, debido a que he vivido en el sur de California durante los últimos cinco años, el bosque ha estado menos presente en mi obra. Ahora estoy rodeado de montañas, colinas y flores silvestres. Pero cuando sí incluyo un bosque, por lo general es un bosque de álamos temblones o abedules. Crecí en Colorado, donde había muchos bosques de álamos en las montañas, y siempre me han fascinado las formas oscuras como ojos en su corteza blanca. En Londres, me encantaron los bosques de abedules por la misma razón. Dado que parte de mi trabajo consiste en situar a figuras queer como parte del mundo natural, en lugar de separarlas de él, me gusta que el bosque pueda devolvernos la mirada. A menudo incluyo pequeñas escenas de ligoteo gay en mis obras más grandes, y me agrada que los bosques de abedul y álamo aporten un matiz voyeurista a estas escenas.

Funciona. Es claro el contraste. Los bosques refieren de inmediato a la plenitud y exuberancia de la vida, donde el dominio racional se ve enfrentado por una realidad que lo excede y desafía.

¿Dónde cabría hallar el componente femenino en tus obras, si lo hay?

¡Pregunta interesante! No he incluido figuras estrictamente «femeninas» en mi obra, aunque algunos de mis modelos se identifican como los llaman ahora: «no binarios». Sin embargo, a menudo elijo intencionadamente posturas para mis figuras que tienen un matiz femenino. Creo que la vía habitual para expresar la sensualidad de una figura masculina es a través de la fuerza y la dominancia, pero a mí me gusta que mis figuras tengan una presencia más ambigua. Aunque las figuras sean musculosas, prefiero dotarlas de una sensualidad más sumisa y tierna, en lugar de una que sea abiertamente masculina. Suele tratarse más del arqueo de la espalda o del enfoque en las nalgas más que en el pene. A veces tomo posturas de estatuas o pinturas femeninas y las reinterpreto con figuras masculinas, sin quitarles nada de la sensualidad original de la pose. Es una mirada más queer sobre la figura masculina, frente a ciertas representaciones del cuerpo masculino sexualizado que encontramos en la historia del arte.

En efecto. Se opera en ellas desde una abstracción evidente de su más patente materialidad. Una afectación intencionada.

¿Cuáles son tus principales influencias?

Me gusta observarlo todo. Algunas influencias constantes serían Matisse, Gustav Klimt, Tamara de Lempicka y Ben Shahn. Siempre hay un poco de Picasso. Consulto mucho el art decó y los murales de los años treinta. Para mi exposición más reciente, estuve mirando mucho las estampas japonesas del período Edo y la serie de Moby Dick de Frank Stella. Ambos tienen una manera única de incorporar distintos patrones y formas en una misma obra, especialmente el elemento de olas o inundaciones en blanco y negro que introduje en esta serie. También he estado observando pintores regionalistas como Grant Wood, el arte popular estadounidense y las tapicerías medievales, que presentan una cierta planificación de ciertos elementos y una claridad narrativa a las que respondo profundamente.

¿Hacia dónde apunta a futuro tu obra?

Creo que el marco en el que desarrollo mi obra —«figuras queer en la naturaleza»— tiene unas posibilidades enormes para explorar y profundizar en distintas ideas. En «Carry It With You» quise indagar más en algunas de las formas problemáticas en que nos relacionamos con la naturaleza, y explorar qué significa eso en el contexto del cambio climático, la guerra, el desplazamiento y ser una persona queer, además de ideas más metafóricas sobre dejar partes de nosotros mismos atrás y lo que llevamos con nosotros. Me gustaría seguir avanzando en esas direcciones y ampliar aún más la idea de lo que significa para mí el «arte queer». Definitivamente, la sexualidad y la representación forman parte de ello, pero creo que es un tema tan abierto que me entusiasma ver hasta dónde más puede llevarme. Actualmente estoy experimentando y leyendo sobre el agua y los ríos, que creo ofrecen muchas posibilidades tanto formales como temáticas por explorar.

¿Qué te gustaría que te pregunte alguien luego de haber visto tu última exposición pictórica?

Creo que me gustaría que alguien me preguntara por qué me centré en la idea de «llevar» para esta exposición. Una de las grandes ideas que moldeó esta muestra fue la lectura de «Two Hearts Dancing» de Eli Andrew Ramer, quien describe a las personas queer como «el Pueblo que camina entre mujeres y hombres, que camina entre noche y día, que camina entre el cielo y la tierra, que camina entre los vivos y los muertos, conectándolos, llevando su belleza de un lugar a otro». Dado que las personas queer nacemos en todas partes y a menudo dejamos nuestras casas, me encanta que esto nos dé el poder de tender puentes entre esas divisiones y conectar lugares y personas. Pero también creo que solemos ser buenas leyendo las señales, alertas a los indicios de peligro y preparadas para marcharnos si es necesario. Así que en esta exposición quise explorar qué elegimos llevar con nosotros si nos vemos obligados a partir. En esta serie, las figuras se van ante inundaciones e incendios, que pueden ser tanto literales como metafóricos. Ante esto, llevan consigo otras criaturas (los burros), flores y haces (o «faggots») de madera. La madera les permite reconstruir, las flores aportan belleza y potencial de nuevo crecimiento, y los burros representan muchas cosas para mí, pero creo que en esencia representan nuestra humanidad. A menudo, en tiempos de crisis y caos, especialmente en el mundo tal como es hoy, corremos el riesgo de perder nuestra humanidad y compasión. Pero me gustan los burros, especialmente el potrillo en «Flood», porque son un recordatorio de la importancia de no abandonar a los más suaves y vulnerables entre nosotros, ni tampoco de dejar atrás las partes más tiernas y vulnerables de nosotros mismos.

[Todas las imágenes, del sitio oficial del artista: J. Carino]

English (original) version:

Materiality and Contrast: A Conversation with J. Carino about His Artistic Work

Although every valuable work of art is valuable for its own eloquence, for its outstanding power to question, and for the way it calls into doubt the very concepts and institutions of the institutional framework from which it emerges and to which it belongs, it is above all valuable for being part of a material communicative phenomenon. This phenomenon consists not only of those two elements, but also of a third: the artist themselves and the observer—real, flesh-and-blood individuals, sensitive and endowed with ideas that are either systematically or unsystematically organized. In this sense, the voice of the one who offers their vision through an artistic medium acquires special significance—not to explain what each of their paintings already expresses in itself, but rather to shed new light on their understanding and interpretation, which entails acknowledging their use of more or less conventional terms, some of which are precisely the ones fundamentally challenged within their work. Indeed, far from a mere search for contradictions, attending to the testimony of the artist demands that we always recognize how the artist’s worldview acquires meaning—intentionally, yet also despite themselves—within a rational framework marked by conflict.

J. Carino kindly offers us his voice here, in response to several questions we posed regarding his most recent work:

What do you yourself say about the geometry used in your paintings? Is its function essential, or rather that of a mere expressive form for something deeper?

I’ve been thinking about this idea a lot, especially in my recent work, and there are a few layers to the geometry in my paintings. On one level, I like to depict rocks, trees, mountains, and human figures with the same approach, which sometimes involves abstracting them into more cubist, fragmented, and geometric forms. I think it creates a world where the boundaries between human and “environment” can be less rigid. It helps blur the line between a figure and a tree trunk, a boulder, or a hillside. On another level, queer people often lead very compartmentalized lives. Because our lives are not accepted everywhere, we cordon off pieces of it for certain people to see in certain situations, and I like to reflect that idea in the compartmentalized and geometric nature of my compositions. They are wild, natural landscapes, but they are broken down into sections of pattern and shape, almost collaged together in some cases, where these areas are kept separate from each other while remaining a part of the whole. One aspect of it I’ve been thinking more about recently, is the way in which this way of depicting the figures in particular, has an almost digital, or polygonal feel to it. In my work, although it is commentary on the modern world, there is very little to suggest that modernity, aside from a speedo tan line or a modern haircut. I think, though, that the geometrical way of depicting the bodies and the landscapes brings an element of our modern, technological world. Even though I’m sometimes showing idyllic edens and their peaceful inhabitants, they still reflect the technologized state and way of seeing the world that is inescapable today. We are all kind of half machine, glued to our phones, while trying to find our way back into being a part of nature again.

The body as matter: here, one moves slightly away from the inherent softness of form and reveals, in the pictorial style, a certain desire to endow it with a different—perhaps more solid—consistency. What are your thoughts on this?

I think my depiction of bodies definitely tends towards solidity and monumentality. I’m inspired by painters like Tamara de Lempicka, Diego Rivera, and Ricardo Martínez de Hoyos who created figures that feel massive and weighty, almost like titans or gods. I like there to be softness in the gesture, or the expression, but I like for the figures to have that kind of heroic quality to them.

What significance do you attribute to the forest, at least in relation to the protagonists of your paintings?

I think, because I’ve been in Southern California for the past 5 years, the forest has been less present in my work. Now I’m surrounded by mountains, hills, and wildflowers! But when I do feature a forest, it is usually an aspen or birch forest. I grew up in Colorado, where we had lots of aspen forests up in the mountains, and I’ve always loved the dark eye shapes on their white bark. In London, I loved the birch forests for the same reason. Because part of my work is about placing queer figures as a part of the natural world, instead of separate from it, I like that the forest can look back at us. I often include little vignettes of gay cruising in my larger works, and I like that the birch and aspen forests provide a voyeuristic aspect to these scenes.

It works. The contrast is clear. Forests immediately evoke the fullness and exuberance of life, where rational control is confronted by a reality that surpasses and challenges it.

Where might one find the feminine element in your works, if present at all?

That’s an interesting question! I haven’t featured any strictly “female” figures in my work, although some of my models identify as nonbinary. Oftentimes, though, I intentionally choose poses for my figures that have a femininity to them. I think the typical avenue for sensuality of a male figure is one of strength and dominance, but I like to have my figures with a more ambiguous presence. Even if the figures are muscular, I like to give them a sensuality that is a bit more submissive and tender, rather than one that is overtly masculine. It’s usually more about the arch of the back, or focus on the butt rather than the penis. I’ll sometimes take poses from female statues or paintings and rework them with a male figure, without removing any of the sensuality of the pose. It’s a queerer gaze on the male form than some of the depictions of a sexualized male body that we get through art history.

Indeed. They operate through an evident abstraction from their most apparent materiality—a deliberate affectation.

What are your main artistic influences?

I like to look at everything! I think some constant influences would be Matisse, Gustav Klimt, Tamara de Lempicka, and Ben Shahn. There’s always a little Picasso in there. I look at a lot of art deco and murals from the 1930’s. For my recent show, I was looking a lot at Japanese Edo era prints and the Moby Dick series from Frank Stella. They both have a unique way of incorporating different patterns and shapes into a single work, especially the black and white flood/wave element that I introduced in this series. I was also looking at Regionalist painters like Grant Wood, American folk art, and medieval tapestry, which have a flattening of certain elements and a clarity to the storytelling that I respond to.

Toward what direction does your work aim in the future?

I think that the framework that I create work within, “queer figures in nature”, has such wide possibilities for different ideas to explore and push on. In “Carry It With You” I wanted to dig a bit deeper into some of the problematic ways in which we relate to nature, and explore what that means in the context of climate change, war, displacement and being a queer person, as well as the more metaphorical ideas of leaving parts of ourselves behind, and what we take with us. I’d like to keep pushing in those different directions, and widening the idea of what “queer art” means for myself. I think that sexuality and representation is definitely a part of it, but I think it is such an open topic that I’m excited to see where else it takes me. I’ve currently been experimenting with and reading about water and rivers, which I think offer a lot of formal and topical areas to explore.

After seeing your latest painting exhibition, what would you like someone to ask you?

I think I would want someone to ask why I focused on the idea of “carrying” for this show. One of the big ideas that shaped this show was reading “Two Hearts Dancing” by Eli Andrew Ramer, who describes queer people as “the People who walk between women and men, who walk between night and day, who walk between the sky and the earth, who walk between the living and the dead, connecting them, carrying their beauty from place to place.” Because queer people are born everywhere and often leave their homes, I love that this gives us the power to bridge those divides and connect places and people. But also, I think that queer people are often good at reading the writing on the wall, alert to signs of danger, and being ready to leave if they have to. So in this show, I wanted to explore what we choose to bring with us if we are forced to leave. In this series, the figures leave in the face of floods and fires, which can be both literal and metaphorical. In the face of this, they bring along fellow creatures (the donkeys), flowers, and bundles (or faggots) of wood. The wood allows them to rebuild, the flowers offer beauty and the potential for new growth, and the donkeys represent a lot of things to me, but I think at the core they represent our humanity. Often in times of crisis and chaos, particularly in the world as it is today, I think we run the risk of losing our humanity and compassion. But I like the donkeys, particularly the foal in “Flood”, as they are a reminder of the importance of not leaving behind the softest, most vulnerable among us, and to not abandon the soft and vulnerable parts of ourselves as well.